Psychological pricing is a huge market research industry.

It’s no secret that the way people perceive your prices affects your conversions either negatively or positively.

Large retailers have spent years and years of research and billions of dollars collectively figuring out how to make consumers more likely to pull out their wallets and stand at the register with their purchases.

But how can we ride the coattails of those big-box retail store’s research and apply the same tactics to our Shopify stores?

In this article, we’re going to dive into some time-tested strategies that you can adopt today to skyrocket your sales.

So, if you’re finding it tricky to get price-sensitive customers to open their wallets and buy, here’s how to help convince them…

Before we get into that, it’s helpful to understand that there are fundamentally three types of buyer personas you must convince:

Buyer Personas

1. Tightwads — “I’m not spending a penny unless you pry it out of my tight-fisted hands.”

Tightwads love to save and loathe spending. This makes them cling onto their money as long as they can before reluctantly parting with it. These are the 24% of people that you need to work hardest to convince because they need serious leverage to be persuaded to open their wallets.

Think Scrooge and you won’t be far wrong. They love their money, as long as it’s sitting safely in an extra secure savings account.

2. Spendthrifts — ”I’m going to spend everything I’ve got… and then some!”

The Shopify store owner’s dream customer—spendthrifts are the impulse buyers we all hope we can hone our Facebook pixel to target on a massive scale. They love spending money, it’s their favorite pastime.

Spendthrifts represent about 15% of buyers and the type of people who are loved by credit card companies. They will keep spending until they max out their card, then reach for the next and keep going.

They’re a cinch to convince, just mention the word “bargain” or “sale” and they’ll tap in their credit card details faster than you can say “minimum monthly payment.”

3. Average Spenders — “If it seems like a good investment, I’ll purchase it.”

This type of buyer represents about 61% of shoppers. They spend what they think is appropriate after carefully weighing up the options, They like to make smart buying decisions and haggle for a discount where they can.

But regardless of the buyer’s spending persona, whenever I’ve analyzed visitor intelligence gathered on my own or client’s sites, price is always an objection that comes up.

The thing to remember here is that even spendthrifts won’t buy if they have objections that go unanswered. So your job as an e-commerce store owner is to answer and overcome every conceivable sales-objection in order to win the sale.

Satisfied, loyal and returning customers are less focused on price. They understand your value and appreciate it. That’s why it’s a good idea to create a customer loyalty program to keep them coming back once you’ve got them in the door.

Have a rock-solid value proposition

This is the prelude to overcoming any price objections for the “average spenders” who make very considered purchases. Without a compelling reason for this type of shopper to buy from you, then chances are, they’ll bounce straight back to Google looking for a cheaper price elsewhere.

Once you’ve established this and provided basic reassurances to overcome any anxieties around trust, you stand a better chance of keeping someone on your site long enough for them to evaluate your prices.

For the tightwads, they’ll likely look at the price first before taking into account your value proposition and trust factors.

If you still haven’t tackled crafting your value proposition, read this.

Tap into your buyers’ wants

Shoppers are more price sensitive to the necessities of life. They are less sensitive to things they want. When was the last time you knew of someone haggling over the price of a new Porsche?

When you tap into the buyer’s wants, price is less of an issue. This is where you’re going to have to hone your copywriting skills.

If your product warrants a long-form sales page like athleticgreens.com then you can do a proper job of talking-up all the benefits to amp-up their desire as well as handling all the sales-objections.

For other great examples of persuasive product descriptions, check out jpeterman.com, firebox.com, and betabrand.com

So without further adieu, let’s get started…

Psychological Pricing Example #1:

Prices without dollar signs

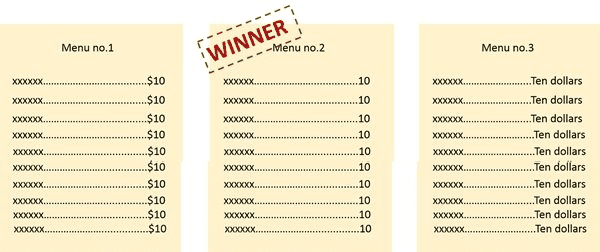

In a Cornell study, guests were given a menu with only numbers and no dollar signs spent significantly more than those who received a menu with either the prices showing dollar signs or prices written out in words.

The hurt of a buyer pulling out their wallet can be triggered pretty easily. In fact, simply having the dollar sign in your price can remind people of that pain, and it can cause people to spend less (Yang, Kimes, & Sessarego, 2009).

What does this tell us? I believe we can infer that when people aren’t reminded of the symbol of their currency, the price carries less significance.

I mean come on, it’s just a number! It’s not like it’s money! It’s a similar effect to when casinos use chips when arcades use tokens, etc

Some themes give you the option to turn off the currency symbol. If not, there’s a good chance you can use a little CSS savvy with the help of a developer and turn off the currency symbol manually.

One foreseeable problem is international customers. There are plenty of plugins that automatically detects where your customer is from, then you can translate the currency to their region without the symbol so that the price is still accurate. (The Shoptimized theme does this automatically.)

Psychological Pricing Example #2:

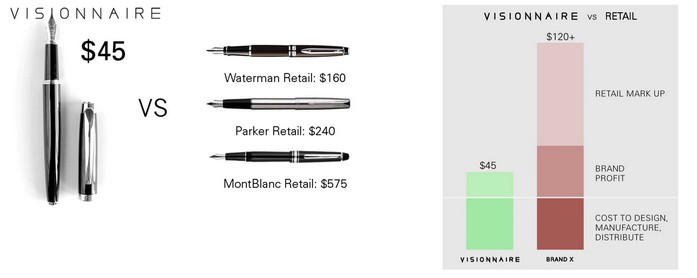

Compare with other competing products

This tactic is only viable if you can shine a light on your products in a way that avoids creating too much curiosity so that people end up disappearing to your competitors’ sites.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #3:

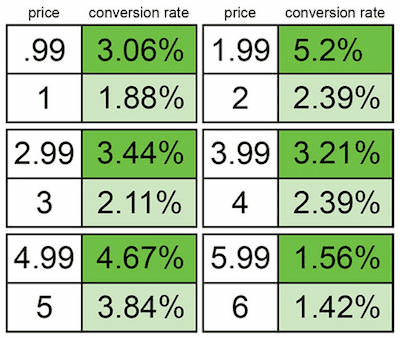

Dollar without cents aka Charm pricing

Shoppers have been trained since they first started spending their pocket money as a kid to associate prices ending in .99 with discounts and bargains. This works even if the actual saving is a pittance.

Removing the change from your prices, also known as “rounded pricing”, has an interesting effect.

Wadhwa and Zhang (2015) found that when prices had rounded pricing – because they are easier to read – work best for emotional purchases.

When consumers can process the price quickly without thinking too much, the price “just feels right.”

But, the opposite can be true. Consumers need more mental resources when understanding non-rounded pricing. These prices would seem to fit more with rational purchases.

Personally, I disagree. I believe that every purchase is an emotional one first and foremost. People justify their purchases with logic later.

There’s also the theory that if you’re concerned about cents then this product is not for you. However, this example seems dated because many software as a service applications online are now using this psychological pricing frequently.

Where can this backfire? Anything that seems to be priced lower.

As the price goes up, you can see a trend of less of a margin between rounded pricing versus regular pricing.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #4:

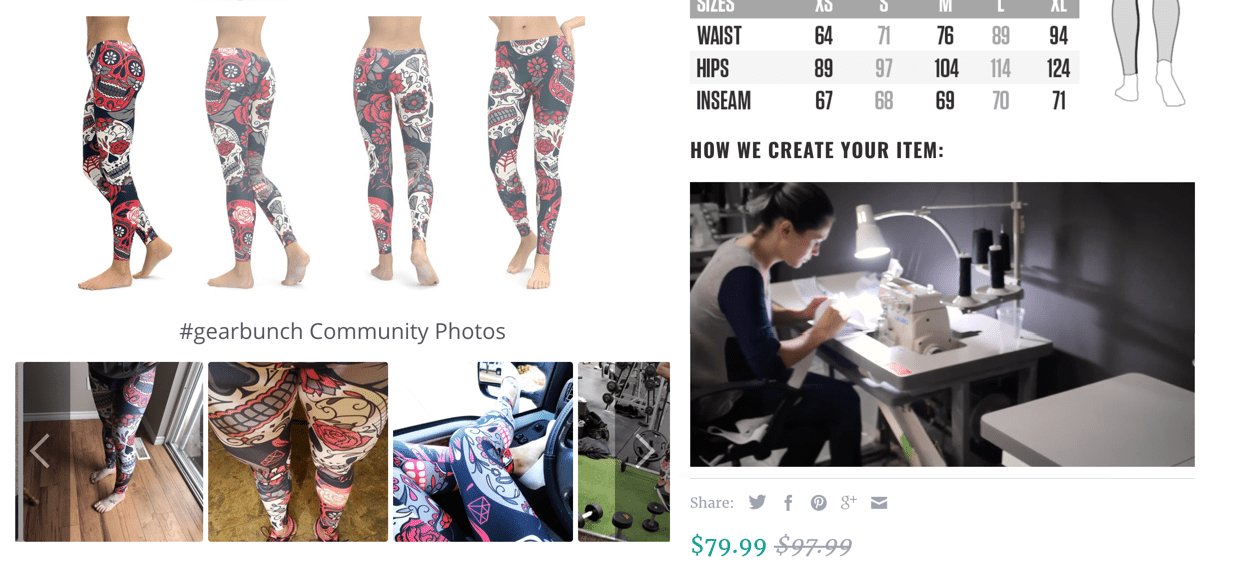

Product before price, “I think it’s nice”

There are multiple facets of what I consider price anchoring.

Do jewelers make it obvious how much each item costs? No way.

Everyone realizes this, but they may not have thought about exactly the reason.

When you see the ring you want to buy your significant other, you know it’s the right one.

Not too many guys go shop in the clearance bin for jewelry. (If they do, they may find themselves shopping for no one)

The reason is this: We aren’t shopping based on the value of the item but more so the attachment to what that item can bring. Happiness, approval, excitement.

In a word, emotions.

Karmarkar, Shiv, and Knutson (2015) conducted a study where they gave participants $40 to shop with. The researchers used fMRI to analyze their brains while they shopped for online products.

What they found is monumental research for online store owners.

The first thing customers see is the most important. Price vs. product.

This single factor influenced the reasoning that people use when deciding whether to buy a product.

When a product was displayed first, the participants based their purchase on whether or not the purchase was something they liked.

When a price was displayed first, participants based their purchase on the economic value of the product.

If you sell luxury products, you want people to base their decision on the qualities and benefits of your product. You don’t want them to consider the economic value. You don’t want them to comparison shop for your business.

So to summarize: for luxury products, show the product, and THEN show the price.

The opposite is true for products of practical use.

The shoppers of the study were more likely to purchase practical products if they were exposed to the price first. With that exposure, people were more likely to appreciate the economic value of the purchase.

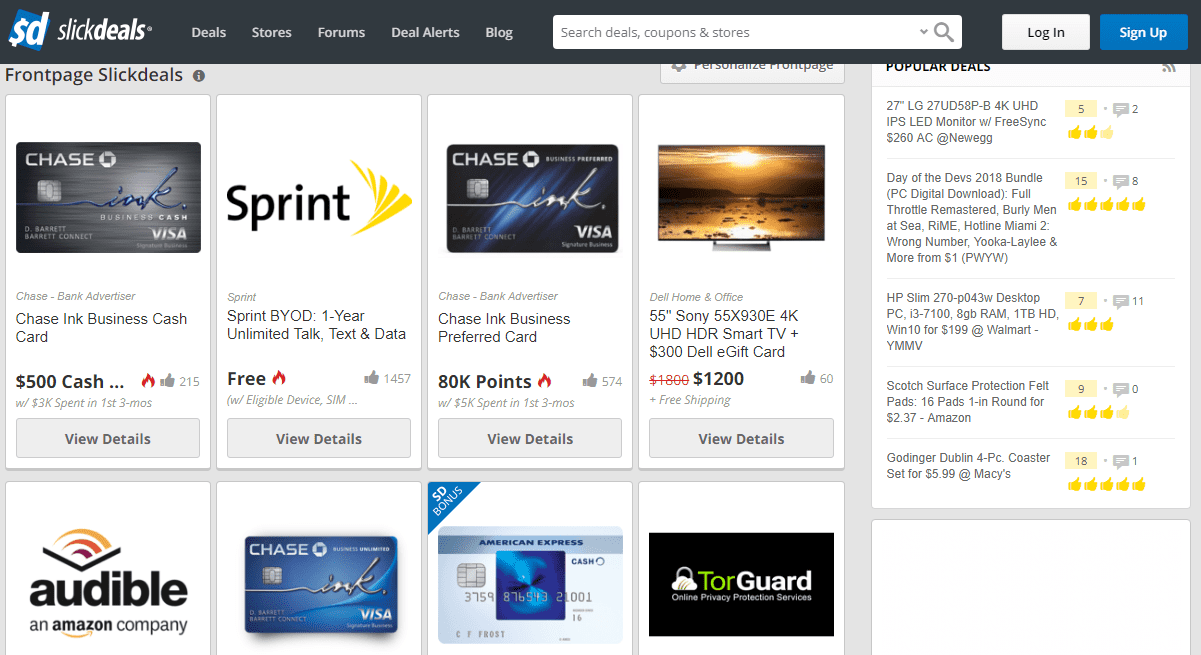

If the price is your selling point, then, by all means, you should be highlighting the price first. Take, for example, Slickdeals.net.

They are dedicated to saving people massive amounts of money. Granted they don’t sell the products directly, but their site is laid out to show the price predominantly first.

But what about when you’re selling something and you don’t want to scrape to sell at the best price to the consumer? (Most of us)

Psychological Product Pricing Example #5:

Avoid surprise shipping costs

There’s nothing that will make shoppers abandon their cart faster than unexpected or unreasonably high shipping costs.

My advice is to eradicate this potential objection entirely and this article goes through this important subject in detail.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #6:

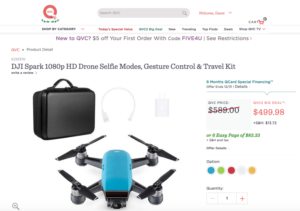

Exposing the buyer to a high price aka Price Anchoring

With price anchoring, sellers always seem to get more earnings out of any deal by starting price negotiations with a high offer to start with (Galinsky & Mussweiler, 2001).

You can anchor a higher number in your shopper’s mind by positioning it where the shopper can see it first. Shoppers who see a higher number before a lower number are often willing to spend more money…

Suk, Lee, and Lichtenstein (2012) tested this idea in a bar.

During an 8-week span (and 1,195 beers later), the researchers switched up the sequence of drink prices.

And guess what?

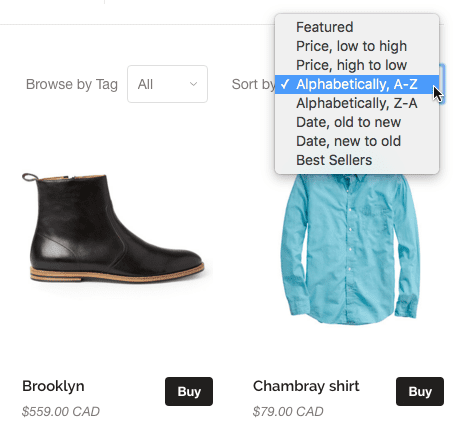

They maximized their sales when they sorted prices from high to low.

Thanks for this tiny change, there was an average of $.24 gained for each beer sold.

I’ll drink to that!

It’s a bit like when I ask my wife, Chrissi if I can go to Japan for a month to train with my Ninjutsu Grandmaster and she thinks I’m outrageous, but when I then ask to go for two weeks, it seems entirely reasonable ?

This high price ‘exposure’ creates an anchor point, which grounds the deal closer to a final number.

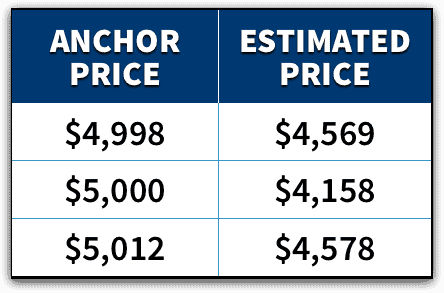

Not only should you start at a high price from the start, but you should use an exact value. In one study, Janiszewski and Uy (2008) asked willing shoppers to estimate the actual price of a new TV based on the suggested retail price — either $4,998, $5,000, or $5,012.

All seems relatively similar, right? You might imagine the answers were all similar. However, there was a noticeable difference in the responses.

When the estimated price is an exact number, we’re less likely to believe that this is the real price of an item.

It has to do with the price seeming more ‘made up on the spot’ rather than if it were a precise figure. It just seems more “likely” that the price is carefully calculated than just slapping a price tag on an item.

So, we can conclude from this that showing your prospective customer a higher price of your item leads them to pay more.

However, there’s even more to it.

It doesn’t just have to be the price of the item itself that a prospective buyer is exposed to.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #7:

Making products seem inexpensive by ANY comparison

Nunes and Boatwright (2004) tested an idea on a boardwalk in West Palm Beach. They sold music CDs.

Every 30 minutes, the adjacent vendor changed the price of a sweatshirt on display — either $10 or $80.

The results? The sweater’s price actually pulled people toward the respective ends of the price spectrum.

When the price of the sweatshirt was $80, shoppers paid higher prices for the CDs. And vice-versa.

This also works for sorting your products and the order in which you show them to your visitors.

Do you know that sort option on your store? Did you know you can sort it by default from “High to Low” prices? It works the same way here.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #8: Any big number will do…

Here’s where stuff gets a little hard to believe.

Anchoring doesn’t just work when you mention higher prices. It works for any number you mention, whether or not that number is a price.

Your prospective buyer doesn’t actually need to think on your anchor number.

In fact, Adaval and Monroe (2002) subliminally showed participants a high number before showing the price of an item. The exposure caused the people to perceive the price lower than the group who did not receive the subliminal number exposure beforehand.

So what’s to be learned here? Show visitors a number, any number, that makes sense to tell them about.

- Join our 2,643 customers and counting

- The only store with over 1,049 products in stock

- We source over 3,508 products for your shopping convenience

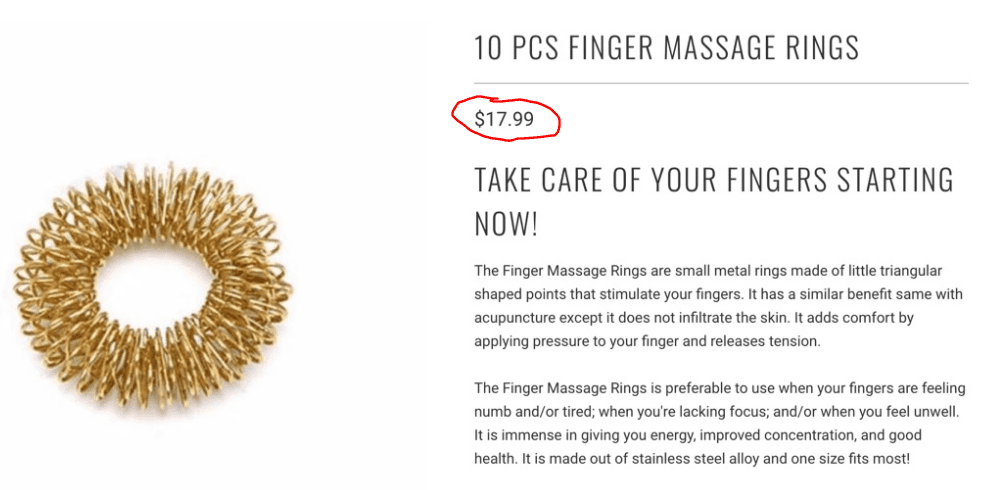

Here’s a small test…what’s better to list on your website?

“$29 for 70 items” OR “70 items for $29”

The 2nd option, “70 items for $29”!

Again, we want to anchor the customer to a higher number. It minimizes the perceived size of your price and maximizes the perceived size of the item amount.

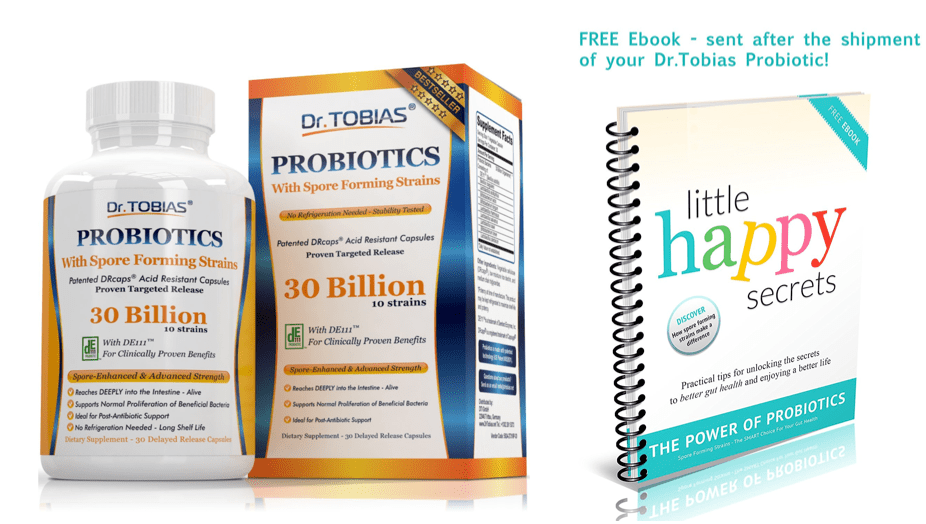

Psychological Product Pricing Example #9: Bundling your products

Creating a product bundle helps shoot down price objections by making “an apples vs apples” comparison of your prices much harder. The trick to this is including something in your bundle that no one else offers.

By offering something small and irresistible to include for an amazing price, you are more likely to convince your buyers to add more to their cart.

The other alternative is to offer a discount on your bundle deals.

Interestingly, neuroeconomic expert George Loewenstein has conducted research that shows ALL customers prefer bundling if it allows them to side-step making multiple purchases.

His findings show we prefer to pay MORE for bundled items if it helps us reduce the number of individual purchases, showing how averse we are to those multiple pain points.

Another way to win on price is to bundle non-tangibles with your products:

- Follow up service

- Extra information (ebook)

- Insurance

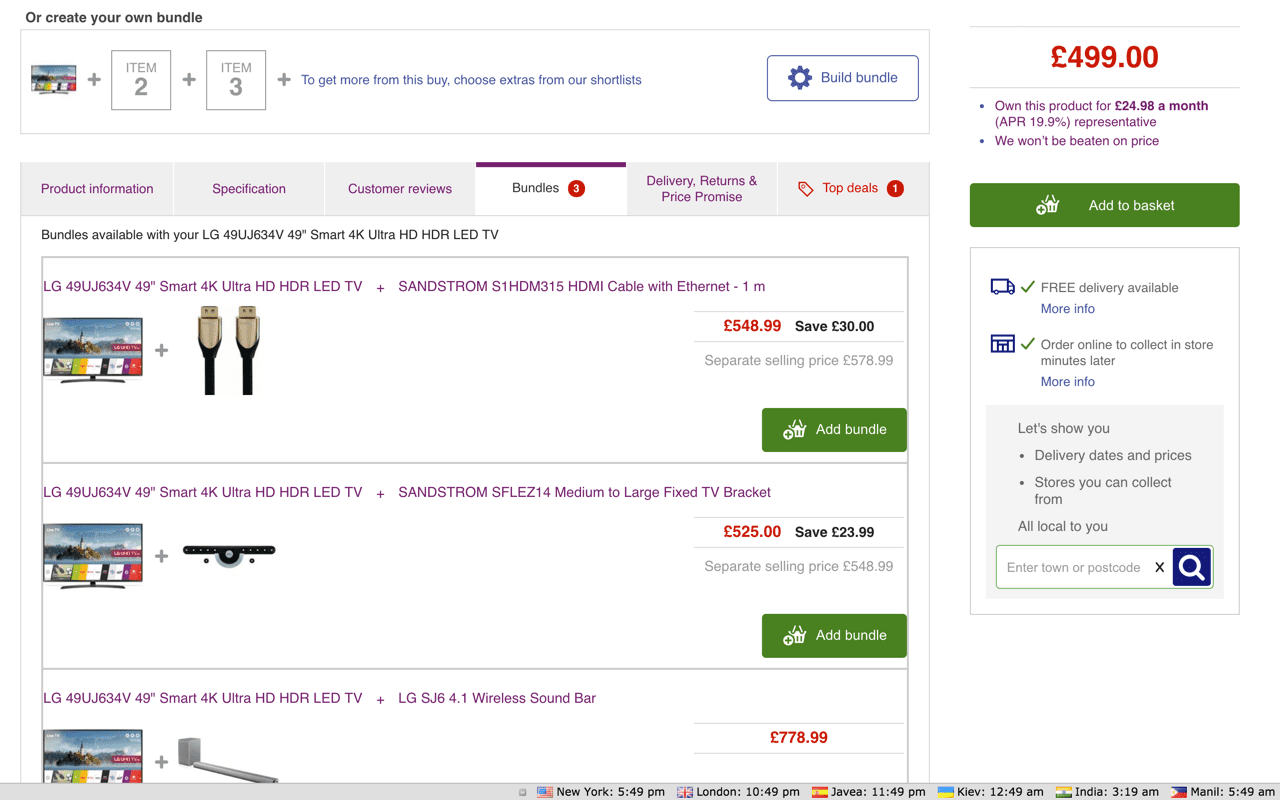

Psychological Product Pricing Example #10: Trivializing the Price

If you sell high-ticket products an easy way to reduce the perceived cost is to break the price down into a daily, weekly, or monthly equivalent.

On the other hand, you could compare the daily cost to something people habitually buy like daily coffee.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #11: Free + Shipping

It’s no secret that free + shipping offers or “tripwire” offers are a surefire way to rapidly acquire new customers and gain market share. But do they bring you the wrong kind of customers?

A big mistake a lot of Shopify store owners make with their tripwires is charging a premium price for the shipping to avoid losing money on the front-end sale. Most of the time unreasonably high shipping costs leave a bad taste in your customers’ mouths and blow the sale altogether or at least mean you’ll never get repeat business.

The better way is to offer reasonable shipping costs and then turn the loss into a profit with an immediate cross-sell or upsell. This can be done either on the checkout page or post-checkout once you’ve secured the initial sale.

This way, your average order value shoots up and you’re in profit sooner and you can afford to spend more to acquire a new customer to stave off your competition.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #12: Buy One, Get One

The new kid on the block in the marketing world is the idea of the “Buy One, Get One Free” offer. Sometimes it is “Buy One, Get One 50%”.

No matter the specifics, they do one thing well – sell stuff.

BOGO is designed to clear inventory that has been sitting around but at a price that you can still make a profit off at a margin above 50%.

Understand that Buy One, Get One Free isn’t the same as “50% off all merchandise”.

The point is to allow someone to buy an item that may be a 50% margin item (you break even) and then they get another item that may be at a 70% margin (you net 20% margin on a sale you otherwise wouldn’t have made).

If you sell items at more than 50% markup, this could be an excellent way to make extra sales.

How about from the customer’s point of view?

Well, there are multiple reasons that Buy One, Get One Free is worlds better than 50% off.

First off, when something is heavily discounted, what’s your first reaction?

Is it broke?

What’s wrong with it?

Why are they trying to get rid of it?

Is it going to fall apart?

Do I even need it?

Our brain instantly devalues the intrinsic value of something simply because our perception of the item has changed due to pricing.

However, when we Buy One, Get One Free…magic happens…

Holy cow! All I have to do is buy one and I get the same full-priced item for free?!

Huffington Post summed this up accurately:

“In 2012, The Economist published a post titled, Something Doesn’t Add Up“.

In it, the author explained that researchers from the Carlson School of Management at the University of Minnesota conducted an experiment to learn more about how consumers reacted to discounts and freebies.

The conclusion was, “Shoppers… much prefer getting something extra for free to getting something cheaper.” Sadly, the explanation for the behavior is less than flattering. “The main reason is that most people are useless at fractions.”

As emotional creatures, people are more inclined to accept free offers than discounted ones. The results speak for themselves. “The researchers sold 73 percent more hand lotion when it was offered in a bonus pack than when it carried an equivalent discount.”

Whether they are right or not, shoppers believe they get a better deal when they walk away with something for free instead of spending less on their overall purchase.”

Are you starting to see the difference in the perceived value of an item based on pricing?

Psychological Product Pricing Example #13: Switch the reference price

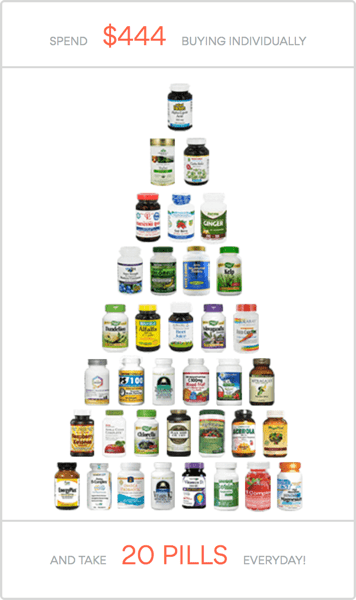

This is an incredibly powerful technique if done properly. This is common in the pharmaceutical space. Instead of allowing shoppers to compare prices with similar products, switching the reference price can bump up the perceived value of your product.

athleticgreens.com switches the reference price from other powdered supplements to avoid the hassle and expense of taking multiple vitamins.

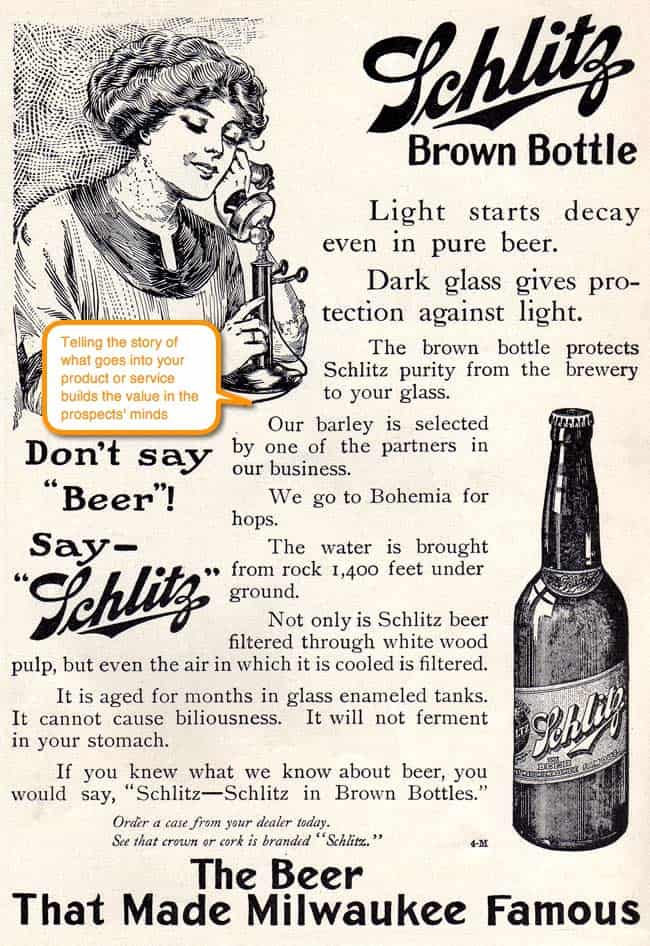

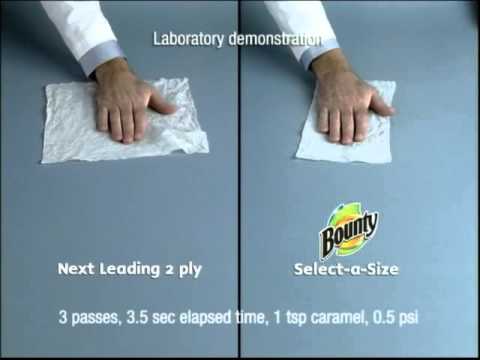

Psychological Product Pricing Example #14: Demonstrate the value

Simply telling shoppers how great your products are to try and justify the price won’t cut it. You need to show them exactly what goes into sourcing or creating your products.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #15:

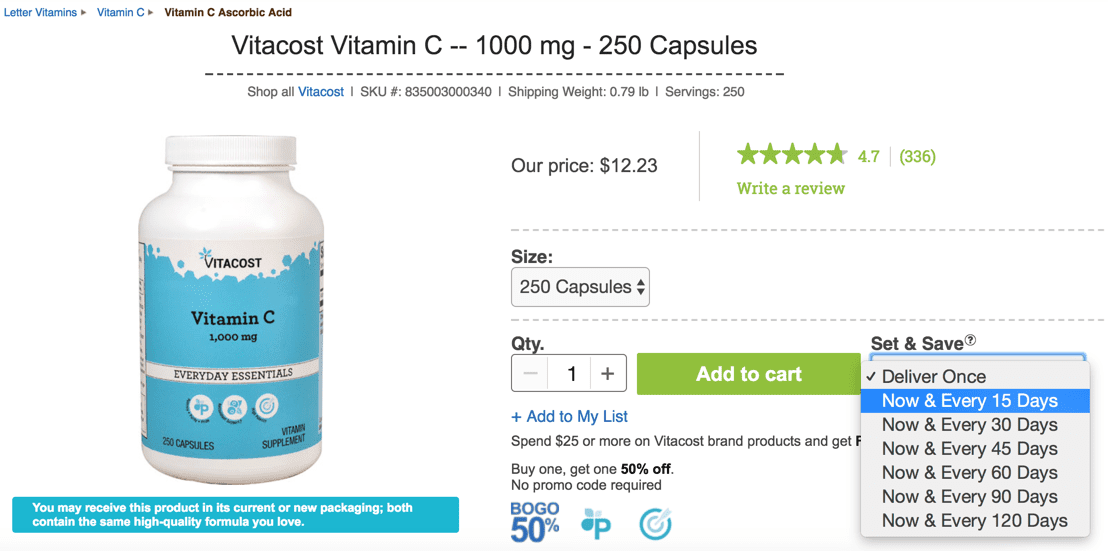

Subscribe and Save

For the bargain hunters that want convenience too, subscription orders are a win-win for you as the store owner and the buyer.

Consumers don’t have to worry about running out of their product because they forgot to make the order. Businesses can better plan and grow with the expected revenue. And with more frequent communication between the buyer and seller about order deliveries each month, there’s the opportunity for upsells.

If you spell out for your customers that they will save time and money in the long run by subscribing, this has a powerful selling effect.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #16:

Splitting up the cost with payment plans

Credit is intangible, shoppers will spend more on plastic than cash. Offering credit is a great way to not only overcome price objections but also to increase your Shopify store’s average order value.

You can start offering payment plans today in your Shopify store with PayPal Credit or Klarna.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #17:

Doing discounts right

Some people advise to never give discounts. To me, this is a little bit of an extremist view. However, discounts can be done pretty poorly.

Let’s explore some ways to do them right.

What looks like the better deal?

When offering a discount, you want it to minimize your bottom line but maximize the perceived value to the customer. You want to make people feel like they’re getting a good deal.

For instance, if you’re selling a $50 widget. Which discount seems better? 20% off vs $10 off?

Doing the math, they’re both equal. But, one discount has a proven advantage.

How can we decide which to pick when pricing a product?

Jonah Berger (2013) suggests following the “Rule of 100.”

Give percentages when you’re discounting a product under $100. $20 (10% off!)

Give actual discounts when you’re discounting a product over $100. $250 ($25 off!)

The idea is to increase the numerical value of the discount itself. This increases the perceived discount to the buyer.

Another tactic, make discounts easy to calculate. So instead of discounting a random number or a specifically priced item. $400 (25% off)

Give a reason for your discount

Another great way to legitimize discounts is to give the actual reason you’re discounting the product you’re selling.

You provide an authentic view of the temporary nature of the discount.

Take this example from the master of persuasion, Robert Cialdini:

“To examine the effects of scarcity and exclusivity on compliance, he instructed his telephone salespeople to call a randomly selected sample of customers and to make a standard request of them to purchase beef.

He also instructed the salespeople to do the same with a second random sample of customers but to add that a shortage of Australian beef was anticipated, which was true, because of certain weather conditions there. The added information that Australian beef was soon to be scarce more than doubled purchases.

Finally, he had his staff call the third sample of customers, to tell them (1) about the impending shortage of Australian beef and (2) that this information came from his company’s exclusive sources in the Australian National Weather Service.

These customers increased their orders by more than 600 percent. They were influenced by a scarcity double whammy: not only was the beef scarce, but the information that the beef was scarce was itself scarce.”

This kind of transparency did not even have to end in a product being discounted. Just honest information about the coming scarcity of a product.

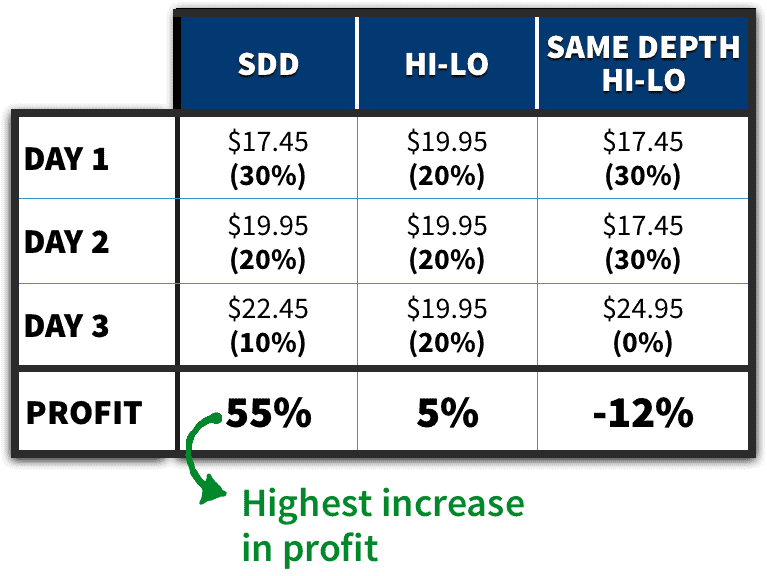

Steadily decreasing discounts

Don’t want to immediately end a discount because you’re afraid of missing customers who didn’t see the discount? But also don’t want to leave the discount around forever as to not provide scarcity?

Tsiros and Hardesty (2010) found an unexpected benefit for a different type of strategy: steadily decreasing discounts (SDD).

Instead of retracting a discount entirely, gradually return the price to the same base level.

The researchers found positive outcomes on multiple metrics. An SDD strategy led to…

- Higher revenue (Study 1)

- Higher willingness-to-pay (Study 2)

- Greater likelihood of visiting a store (Study 2)

The researchers even conducted a field study. Over a 30-week span, they alternated between three strategies for a $24.95 wine bottle stopper at a kitchen appliance store.

The researchers even conducted a field study. Over a 30-week span, they alternated between three strategies for a $24.95 wine bottle stopper at a kitchen appliance store.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #18: Prestige Pricing…No Discounts Here

Discounts are a double-edged sword. When you end a discount, you could cause a competitor to win the prospective customer’s business. Or to wait around for the next time you discount the product.

What can be done to stop this from happening? And what causes it to be more likely to happen?

The answer lies in the message and positioning of your brand and products — whether it’s high quality or low quality (Wathieu, Muthukrishnan, & Bronnenberg, 2004).

If a brand has the position that they do not generally compete on price they attract an ‘elitist’ or ‘premium’ buyer. However, if they begin competing on price: customers start to notice. And they start to pay more attention to the price.

So what can we learn?

If you compete on price…feel free to give discounts. Which most dropshippers have enough of a margin on big times to provide discounts. As long as you’re minding the Minimum Advertised Price.

If you’re competing on quality, you should try to limit discounting too much as possible. Instead, focus on the qualities and attributes of your product.

Psychological Product Pricing Example #19:

Sell time over money

Here’s an interesting study conducted by Jennifer Aaker, the General Atlantic Professor of Marketing at Stanford Graduate School of Business, that shows how consumers value time more than money.

The research involved setting up a lemonade stand with 3 variations of signage:

- “Spend a little time and enjoy C&D’s lemonade” (focus on time)

- “Spend a little money and enjoy C&D’s lemonade” (focus on money)

- “Enjoy C&D’s lemonade” (neutral sign)

The results ram home the importance of writing benefit-focused copy…

The first sign not only attracted twice the amount of customers but surprisingly they were also willing to pay twice as much for the lemonade as well.

It could be argued that money will always be thought of in a negative way because consumers are reminded of the cost of acquiring a product rather than the pleasure of consuming it.

So with this in mind, a follow-up study was conducted by Aaker and her team where they took a poll at a free concert. Even though the concert was free, people had to wait in long lineups to get good seats.

The research team asked the attendees one of two questions: “How much time will you have spent to see the concert today?” or “How much money will you have spent to see the concert today?”

In most cases, asking specifically about time increased participants’ favorable attitudes toward the concert. In fact, those who had incurred the most “cost” (standing in line the longest) rated the concert best of all.

So what are the implications of this research? According to Aaker:

“One explanation is that our relationship with time is much more personal than our relationship with money. Ultimately, time is a more scarce resource—once it’s gone, it’s gone—and therefore more meaningful to us. How we spend our time says so much more about who we are than does how we spend our money.”

Specifically discussing the concert study Aaker noted:

“Even though waiting is presumably a bad thing, it somehow made people concentrate on the overall experience.”

So how does this apply to overcome price-objections for your Shopify store?

When a product is already of good value, emphasizing the time you’ll enjoy by using it (or the time it will save you) is likely more persuasive than focusing on the monetary savings.

But be warned, if you’re selling luxury goods, emphasizing time may fail according to professor Mogilner: “With such ‘prestige’ purchases, consumers feel that possessing the products reflect important aspects of themselves, and get more satisfaction from merely owning the product rather than spending time with it.”

So, keep in mind that premium goods with premium prices should emphasize their quality and ignore the time saving or enjoyment of time.

On the other hand, if you’re selling price-sensitive products, future-pace your shoppers into seeing themselves enjoying the time spent or the time saved with your products, rather than putting all the focus on the price.

Conclusion

If there’s one thing you can count on as a Shopify store owner, it’s that consumers will always want lower prices. And once a consumer spends money online, he wants immediate gratification.

So for an online retailer, there’s nothing more important than price and availability.

The Shopify stores that will win at e-commerce will offer products at low cost and deliver them quickly—and, often, free of charge.

It takes just a few clicks for shoppers to figure out the market price for any item on the internet. You don’t have to be the cheapest on all your products all of the time. But you should be rock-bottom on those items your customers will use to judge you. Consumers are pretty savvy; for the most part, they won’t pay more than they have to. Never forget this.

What Next?

This is an action-packed article with a ton of information about Shopify pricing. There’s no way you can implement it all at once. So just play around with using these concepts and test what works compared to your baseline.

If you’re still having trouble getting your products out the door and you’ve changed your pricing, you may want to consider that pricing is not your issue. You might want to give your conversions a lift and checkout the best converting Shopify theme, Shoptimized™.

Leave a comment below and let us know which pricing example you plan to implement in your store!